|

In the week before the 2008 Michelin guide was published in the UK, Jan met Pierre Gagnaire at Sketch to talk about life, restaurant guides and why he would be a terrible critic himself. This article was first published in the Financial Times. In the week before the 2008 Michelin guide was published in the UK, Jan met Pierre Gagnaire at Sketch to talk about life, restaurant guides and why he would be a terrible critic himself. This article was first published in the Financial Times.

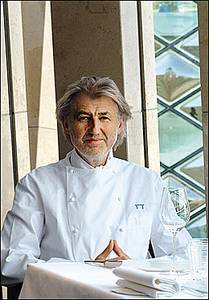

Pierre Gagnaire smoothes back his hair with both hands, a gesture which reveals the cuffs of his crisp Pink shirt and the fact that he has left his cufflinks behind in Paris. 'Look at this, it is plastique ,' he cries, showing one of the makeshift studs keeping his sleeves together. He is amused by his own forgetfulness, even if one might have assumed the sartorial result to be deliberate.

After all, his business partner Mourad Mazouz has just walked by wearing his jacket inside out, and waiters dressed as Victorian urchins used to dispense soup from white vinyl trolleys in one of the restaurants here. No, nothing is ever quite as it seems in madcap Sketch, an avant-garde establishment where two restaurants, two bars, an art gallery and a patisserie are housed in a listed 18th-century building in central London.

On flying visits here from his main base in Paris, Gagnaire oversees the food operation and Mazouz takes care of the magic. "I am responsible for all," says Gagnaire, expansively. "So I like to give a good sandwich, a good burger downstairs, but also a good lobster and a good côte de boeuf upstairs."

The Library, Sketch's top-floor dining room, already has one Michelin star. When the Michelin guide is published next week, Gagnaire is hoping the Library will have two. "They are important," he says. "I am hoping for a good result." He has seven stars in all; scattered throughout an empire that takes in Hong Kong, Paris, Tokyo and London, where we are sitting on blood-coloured sofas next to curtains made of crystals.

"Michelin stars are a symbol of quality," he says. "You know, I have been doing this job for 43 years. And for most of that time I have had to work with such a noise; Michelin, restaurant guides, restaurant critics, this magazine and that." He puts his hands to his temples to keep out the imaginary din. "You would go insane inside your head if you listened to it all. But Michelin can still be exciting. And they take their work very, very seriously."

A mobile phone suddenly flashes into life, its ring tone the sound of a knuckle tapping on a window. The 58-year-old chef seems cheerful and relaxed; his feet tapping in his chisel-toed Fratelli Rossetti lace-ups, his beautifully cut hair just so, his priestly good looks seasoned by the spicy, low aroma of his Thierry Mugler cologne. He looks exactly like the jazz aficionado he is: loose and amused, with a palpable sense of peace that is unusual to find in a chef of his standing.

Today, he's zipped up inside a blue cashmere Hermès sweater; a gift to him from the company. Hermès give him free stuff? Of course they do. Gagnaire is a king of Paris, regarded by many one of the greatest chefs in the world.

On the stroke of noon next Wednesday, the British restaurant industry will begin a dreaded annual ritual. In kitchens up and down the country, there will be the traditional gnashing of teeth, the popping of corks, the wringing of hands and the tearing of hair. While this may soundnot unlike the preparation for a dish of lièvre à la royale, it is, in fact, something much more important than that. This yearly convulsion of joy or despair marks the January publication of the Michelin Guide to hotels and restaurants in Great Britain and Ireland, our catering business's equivalent of Booker Prize gravitas touched with a hint of Nobel.

From its undistinguished UK head office in Watford, Michelin distributes its annual benediction; an imprimatur of varying degrees of excellence measured out in a bewildering array of symbols including stars, bibs, crossed knives and forks of different colours and, sorry, is that a chimney? Yes, the odd thing about Michelin is that, despite recent improvements and its undoubted influence, the guides themselves remain about as user-friendly as the Dead Sea Scrolls. The paper is flimsy, the print is tiny and the fact that it originated as a touring guide is a joke, really, because you have to know where the restaurant is in order to locate it in the book. Yet it is hard not to admire that obduracy: it is so deliciously French.

Twinkle, twinkle little star...

André Michelin, a tyre manufacturer, published the first guide in 1900. The original aim was to encourage motorists to find decent lodgings and eats while touring around France, and to wear down their tyre rubber while they were at it. It has come a long way since then. In the past few years, under the energetic, expansionary leadership of its new director Jean-Luc Naret - who joined in 2003 - Michelin has been assiduously building up its brand, powering into new territories in America and Asia as the guides extend global reach.

"It took Michelin 105 years to realise there was something on the other side of the big sea," jokes Naret, whose background in luxury hospitality - he was once the manager of the Sandy Lane hotel in Barbados - has prepared him well for the rigours of pushing the guides into 22 countries at the last count. If you can cope with the historically rigorous demands of the film director and food critic Michael Winner complaining that the breakfast eggs at the Calypso Buffet aren't hot enough, then you can cope with anything that catering can throw at you. Following the recent publication of American city guides and a new Tokyo guide last year, it is clearly Naret's intention to make Michelin the benchmark by which restaurants are rated all over the world; first on the list are more city guides in North America and Asia. "If a chef says to me, 'what do I have to do to get a star?', I say to him, 'you do your job and we will do ours'," says Naret. "Don't ever try to get a star. That is like an actor trying for an Oscar; it will never work."

The new British rankings will be kept secret until their unveiling on the Michelin website at midday on January 23. Then a kind of culinary hell breaks loose, as the newly promoted and freshly demoted find various ways to assuage their triumph or despair. Will Gordon Ramsay hang on to his three stars at Royal Hospital Road? Will the Gavroche go up or the Waterside go down? Has Michelin overcome its bias towards French restaurants that serve amuses bouches of soup in tiny cups and fold their starched napkins into croissant shapes? These are the questions that have consumed restaurant nerds for months, although Derek Bulmer, editor of the UK guide, is giving little away.

"Will there be shocks? What can I say? I can't answer yes or no to that because that will get you all guessing," he tells me. "All I can say is that there is a jolly good sprinkling of new stars. It is interesting because we never look for the same number of new one-stars, but about the same amount seem to bubble up every year."

That would suggest we can expect about a dozen or so new stars; good news for diners and chefs alike, as the stars are much coveted and bring a welcome business boost. When the Crown at Whitebrook, a hotel restaurant in the Wye Valley, Monmouthshire, was awarded its first Michelin star last year, turnover increased by 45 per cent practically overnight. "It was major," says the Crown's head chef James Sommerin: "It made a huge to difference to us."

In 2001, Tamarind in Mayfair, central London, was one of the first Indian restaurant in Britain to receive a Michelin star. Head chef Alfred Prasad says: "Business went up by at least 15 per cent in that first year. It might have been even more. It was hard to judge, because we had to keep turning down bookings." Pierre Gagnaire, too, reports an increase in business of 20 per cent for every star he has gained. "No one could call that an insignificant amount," he says.

Would you like some knee-jerk with that, sir?

But if Michelin remain the most authoritative and well respected of all the restaurant guides, some do have issues with its working practices. Criticisms include the suggestion that it is sometimes too slow to award deserving new restaurants with stars, and far too lax about withdrawing them when standards slip, perhaps seeing this elimination as admitting to a mistake.

Not true, says Derek Bulmer: "We take our job very seriously. We give an awful lot of consideration. If there is an element of doubt, we will always err on the restaurant's side because we know the effect it will have on their business.

"We don't have a knee-jerk reaction to one bad meal. It took a series of good meals to win the star in the first place; it takes a series of bad meals to take it away."

Yet can Michelin continue to be all-powerful in a world and to a customer base that are turning to the internet for foodie information? In the olden days there was really only Michelin, Gault-Millau and Egon Ronay - and the latter two are now more than past their prime. To this number have been added the Good Food Guide, the Time Out Guides, the weekly contributions of newspaper and magazine restaurant critics, guides such as Hardens and Zagat (which is considering selling, if anyone wants to start the bidding at £102m). Not to mention the deafening roar from restaurants themselves, from amateur critics, bloggers, food websites, freaks and the chef's mum who keeps posting how brilliant he is on his dining-out website.

Of course, I like to think that my own tiny website (www.areyoureadytoorder.co.uk) is a snowflake of purity and witty independent opinion in a blizzard of misinformation and hype, but then again, I would, wouldn't I? Derek Bulmer of Michelin thinks there is room for all of us.

"The more voices, the better," he says. "I don't like to criticise other guides. I think there is a place for everybody, room for us all. I read all the restaurant critics; they are a good source of information, as are chat rooms and websites like www.egullet.com. They are all valid."

At the top end of the market, the economics of haute cuisine can be punishing. Chefs who have been burned by them know that Michelin stars are not fixed points in the restaurant firmament, but something more mutable and dangerous. Like real stars, they can fizzle and burn out. Sometimes they will shine brightly for years. Sometimes they are a curse. Pierre Gagnaire has direct experience of this: in 1996 he was the first chef in a century of Michelin history to go bankrupt when he had attained their highest accolade of three stars. "A thread still connects me to those years," he says today. "I learned something. I learned that Mr Hilton was right when he said 'location, location, location'. My restaurant was in St Etienne, an industrial town like Manchester or Liverpool, where there were no tourists." He shrugs. "And I began to be expensive."

The same year that Gagnaire went broke, another three-star restaurant near Annecy in east central France closed for a short time because owner and chef Marc Veyrat was badly in debt. An amnesty from the bank allowed him to reopen a month later and today he continues to flourish. In 1998 another three-star chef, Bernard Loiseau, coped with his debt mountain by going public and listing his Burgundy restaurant, La Côte d'Or, on the Paris Stock Exchange. "I am a happy man,'' he told a journalist at the time. "I have provided for my future and created something that will last after me.''

Five years later he committed suicide. Gault-Millau had recently downgraded his restaurant by two points and there were also rumours, which proved to be untrue, that Michelin was going to remove one of his three stars.

So in the end, Gagnaire was one of the lucky ones. He moved to Paris and, with pleasing symmetry, regained his three stars in three years. He was one of the survivors. "I never wanted to be a chef," he says. "It was the family business. So it was expected of me. I had a toque on my head when I was five years old. In the end, it worked out well. But it has been a long journey."

And, he confesses, he himself would be no good as an inspector. Even though he has regularly been coming to London for at least four years, he has never been to a restaurant in the city. Not even out of curiosity.

"I don't like to. Tonight, I break a habit and go to Le Gavroche because I like Michel Roux. But I would never go to criticise of judge or say 'look at this, I hate that; oh no, terrible'. I just go to see my friends."

- 'Reinventing French Cuisine' by Pierre Gagnaire is published by Stewart, Tabori & Chang.

|

Bookmark this article with: